SNAP benefits are flowing again, but for rural families across Missouri and Kansas, the ground beneath them remains unstable. New work requirements that took effect Nov. 1 are creating compliance challenges unique to rural areas, while food banks are still recovering from a 43-day government shutdown that exposed how little margin rural communities have when federal systems fail.

The convergence of policy changes and administrative chaos has left rural families navigating a fundamentally altered landscape—one where the distance to a caseworker matters as much as the distance to a grocery store, and where proving you’re working enough hours can be harder than finding the work itself.

“It’s nearly impossible to make up the gap that SNAP is leaving us, but we’re doing everything we can to make sure that we are easing this burden for folks,” Elizabeth Keever, chief resource officer at Harvesters, a regional food bank in Kansas City, Missouri, told NPR in November. “It’s just this really scary moment where there’s a lot of uncertainty.”

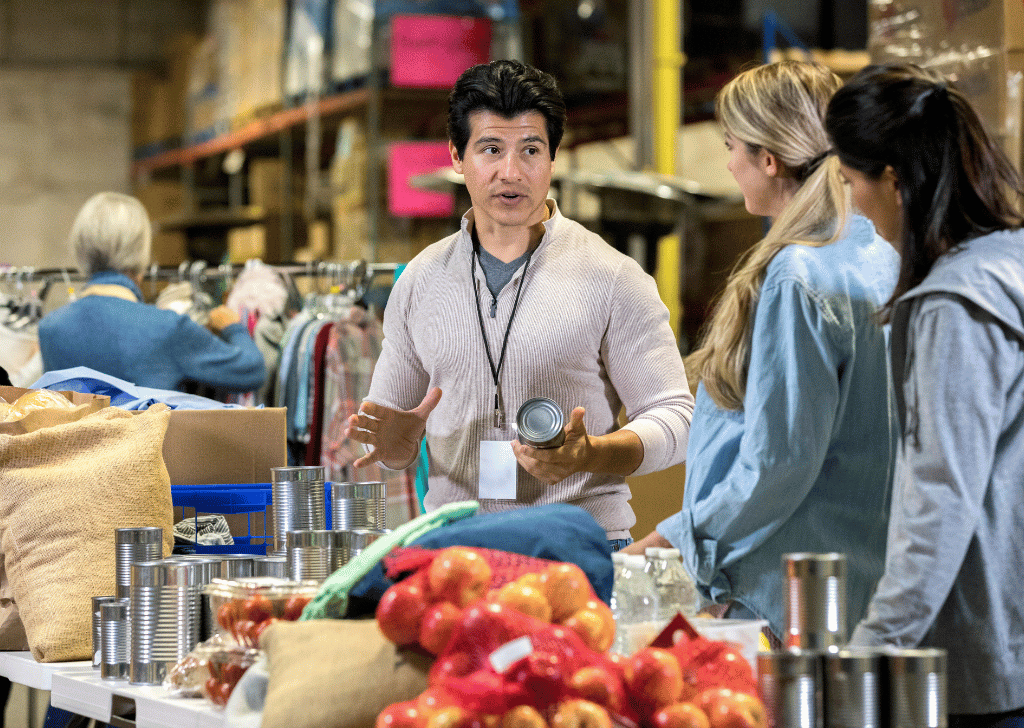

“It’s nearly impossible to make up the gap that SNAP is leaving us, but we’re doing everything we can to make sure that we are easing this burden for folks,” Elizabeth Keever, chief resource officer at Harvesters. (Photo source: Canva)

The Present Challenge

Nearly 655,000 Missourians and 188,000 Kansans receive SNAP benefits each month. Starting Dec. 1, state agencies began verifying that able-bodied adults without dependents under age 14 meet new work requirements: 80 hours per month of employment, training, or volunteer work. The requirement now extends to adults up to age 64, and eliminates previous exemptions for veterans, people experiencing homelessness, and young adults who aged out of foster care.

For rural residents, compliance presents obstacles that don’t exist in urban centers. Missouri’s statewide unemployment rate stood at 4.1% in September 2025, but that figure masks significant rural variation. Hickory County had the highest unemployment rate in Missouri at 7.5% as of August 2025. Even in counties with lower official unemployment rates, finding 80 hours of monthly work remains challenging, where job openings are scarce and part-time positions dominate.

According to the Food Research & Action Center, rural areas face higher rates of part-time employment, fewer job openings, and limited access to childcare and transportation. Rural job growth averaged just 0.3% per year from 2019 to 2023, well below the national rate. By 2023, nearly half of rural counties had yet to recover pre-pandemic employment levels.

In Missouri’s Ozark County, where the food insecurity rate reaches 21%, finding 80 hours of work each month can mean driving 30 miles or more to reach employers. In Dallas, Wright, Texas, Howell, and Oregon counties, one in four children face hunger. These same counties lack the density of volunteer opportunities available in cities, and workforce training programs may require travel to regional centers.

“In this now newly older adult population who aged out of the workforce, it’s very hard at age 62 to jump into a new career and get hired and trained up,” Lucas Caldwell-McMillan, chief of policy staff at Empower Missouri, a nonprofit advocacy organization, told The Beacon. “And I think the same thing that took away this exemption for veterans—there are lots of programs to help veterans, but still not enough.”

The administrative burden falls unevenly as well. Documentation of work hours must be submitted regularly, but rural residents may live 20 to 30 miles from the nearest Department of Social Services office. Limited broadband access complicates online submission. Missouri’s overwhelmed SNAP system has been ruled “broken and inaccessible” by a federal judge, with some offices staffed by only a single employee, according to court documents. These capacity constraints mean longer wait times for rural residents who must travel farther for in-person appointments.

“In this now newly older adult population who aged out of the workforce, it’s very hard at age 62 to jump into a new career and get hired and trained up,” Lucas Caldwell-McMillan, chief of policy staff at Empower Missouri. (Photo source: Canva)

What Food Banks Are Seeing

Food insecurity in Missouri was already climbing before the shutdown. The Missouri Hunger Atlas 2025 documented an increase in Boone County’s food insecurity rate from 11% in 2023 to 15.2% in 2025, according to KBIA. Statewide, 951,330 people face food insecurity, representing 15.4% of the population. In rural service areas, the numbers are higher—one in five children on average, but one in four in counties like Texas and Howell.

Food banks entered November already stretched. Then came the spike in demand during the shutdown. Harvesters, the regional food bank serving northwestern Missouri and northeastern Kansas, saw demand at partner pantries and mobile distributions roughly double during the benefits pause. The organization invested $500,000 from donors to purchase additional food, which was distributed within days.

“For every one meal that we provide, SNAP provides nine,” Keever told the PBS NewsHour in early November. In Jackson County, Missouri alone, monthly SNAP benefits exceed the food bank’s total annual fundraising.

That structural reality—food banks provide roughly 10% of food assistance while SNAP provides 90%—means charitable organizations cannot replace federal benefits; they can only supplement them. The shutdown proved the point. Gateway Food Pantry in Arnold, Missouri, reported a 33% increase in demand from the same period in 2024, serving more than 300 families in a single week. The increase followed a tornado and the Boeing strike that had already pushed local resources to capacity.

Now, as food banks monitor for increases tied to the new work requirements, they’re doing so from a depleted position. Supplies purchased during the shutdown have been distributed. Donor fatigue sets in after crisis response. And the holiday season, always a high-demand period, arrived before recovery was complete.

“It’s going to be really hard. It’s going to be a struggle,” said Michell Jones, who works in the donations department for Operation Breakthrough in Kansas City and is a former SNAP recipient, told KSHB 41. “When I was on it, I looked forward to it every month.”

The Week That Revealed the Cracks

Between Nov. 6 and Nov. 12, families experienced a whiplash of guidance that illustrated what happens when federal support systems encounter dysfunction during a crisis.

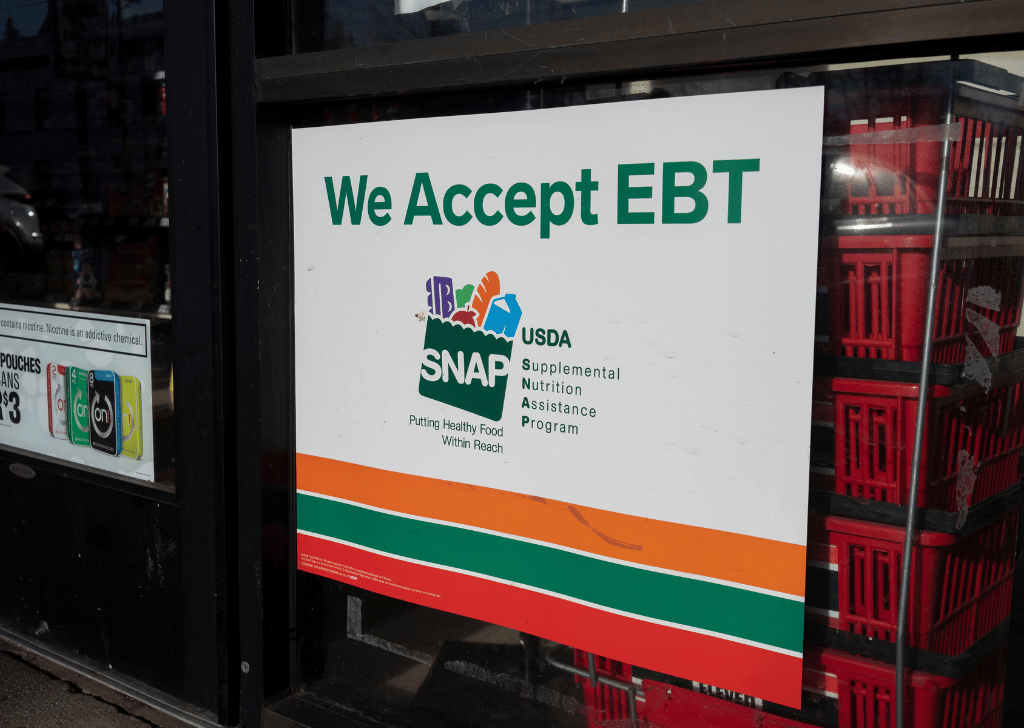

On Nov. 6, a federal judge ordered the Trump administration to fully fund November SNAP benefits by the following day. States began preparing to issue full payments. Some recipients in states like Pennsylvania woke up on Nov. 7 with benefits already loaded onto their EBT cards.

That evening at 9:17 p.m., the Supreme Court issued an administrative stay blocking full payments. By Nov. 9, the U.S. Department of Agriculture ordered states to “immediately undo any steps taken to issue full SNAP benefits for November 2025.” States that had already transmitted full payment files to EBT processors were told their actions were unauthorized.

The result was state-by-state chaos. Some families received full benefits. Some received partial payments at 65% of normal amounts—or less, depending on how benefits are calculated. Some received nothing. Wisconsin overdrew its federal letter of credit by $20 million. North Carolina issued partial benefits to more than 586,000 households on Friday morning, prepared to issue full benefits over the weekend, then had to stop. Maryland’s governor called it “intentional chaos” with “no clarity at all.”

For rural families, the confusion was compounded by geography. Checking your EBT card balance multiple times daily doesn’t help if you live 30 miles from the nearest grocery store and need to know how much you’ll have before making the trip. Gas to drive those miles costs money. A wasted trip means choosing between making a second attempt or going without.

The shutdown ended Nov. 12. Benefits were restored. But the episode exposed how quickly rural food security infrastructure can buckle—and how little backup exists when it does.

Checking your EBT card balance multiple times daily doesn’t help if you live 30 miles from the nearest grocery store and need to know how much you’ll have before making the trip.

The Coming Year

State agencies are now in the process of reviewing SNAP households for work requirement compliance. Most states began Dec. 1, though implementation varies by county and individual recertification schedules. Recipients newly subject to requirements must demonstrate compliance by March 1, 2026. The first month when individuals could lose benefits due to noncompliance is June 2026.

The Congressional Budget Office projects the changes will reduce SNAP spending by $285.7 billion from 2025 to 2034. In Missouri, officials estimate 150,000 individuals are at risk of losing some portion of their benefits, with 68,000 potentially losing all benefits.

For rural counties already operating with shrinking tax bases, the economic impact extends beyond individual families. SNAP dollars generate $1.80 in local economic activity for every dollar distributed, according to USDA research. When benefits decrease, grocery stores see reduced revenue. In communities with only one store, that reduction can mean the difference between viability and closure.

Missouri already has approximately 100 food deserts in both rural and urban areas, according to Empower Missouri. The closure of grocery stores creates cascading effects. Without a nearby market, families rely more heavily on convenience stores, which offer limited fresh food options and higher prices. The increased travel distance for groceries drains already tight budgets. And for those who lose SNAP benefits due to work requirement complications, the nearest food pantry may be even farther than the nearest grocery store.

The Data We Won’t Have

One additional challenge will be measuring these effects going forward. In September 2025, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced it would discontinue its annual Household Food Security Report, which has tracked hunger and food access for decades. The Trump administration labeled the report “redundant, costly, politicized, and extraneous.”

The 2024 report was the last comprehensive federal survey on food security. It showed that 8% of white households face food insecurity, while 21% of Black households and 16.9% of Hispanic households do. Those disparities exist in both urban and rural areas, but rural communities lack the diversity of support services available in cities.

Without consistent federal tracking, states and advocacy organizations will need to develop their own measurement systems to understand how policy changes affect food access. The Missouri Hunger Atlas provides county-level data for the state, showing patterns that would otherwise remain invisible in statewide averages. Similar efforts will become more critical as federal data disappears.

What Stability Requires

December brings a return to normal payment schedules, but not to stability. Rural families face ongoing uncertainty about whether they can maintain benefits under requirements designed without rural realities in mind. Food banks are preparing for potential increases in demand while still recovering from November’s surge. And grocery stores in marginal markets are calculating whether reduced SNAP spending will push them toward closure.

In an article by St. Louis Public Radio, House Minority Leader Ashley Aune, a Kansas City Democrat, called the recommendation to stretch SNAP benefits “insulting” when it was issued during the shutdown. “If you’re looking at how expensive it is to live right now, between tariffs and all of the costs of living rising around us, it’s an absurd proposition,” Aune said.

The question is not whether rural food security systems can handle another crisis like November’s shutdown. The evidence from those 43 days suggests they cannot. The question is whether the systems in place now—with new requirements, reduced capacity, and less federal oversight—can maintain even baseline function.

For families in rural Missouri and Kansas, the answer matters every month. It matters when deciding whether to drive 30 miles to document work hours with a caseworker. It matters when calculating whether remaining benefits will stretch to the next payment date. And it matters when the nearest grocery store closes, turning a one-mile drive into a 20-mile round trip.

The safety net has not disappeared. But it has frayed. And rural communities are discovering that when the margin for error shrinks, geography becomes destiny.